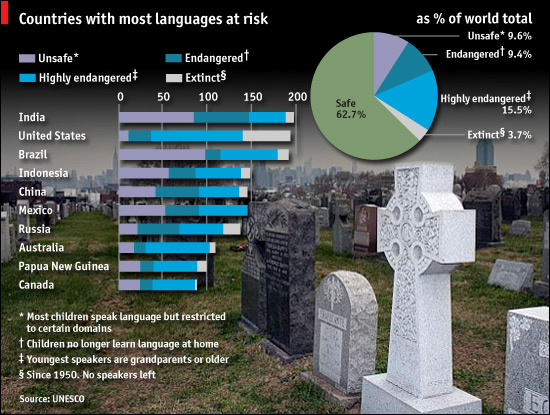

Speaking in fewer tongues: A third of the world's languages are at risk

Daily chart

March 17th 2009

From Economist.com

Around a quarter of the world's population speaks just three languages: Mandarin, English and Spanish. But out of the 6,700 of the world's identified languages, nearly 2,500 are deemed at risk according to UNESCO, the UN's cultural body. The imposition of a colonial language long ago in big countries such as Brazil and America is still endangering the diversity of native tongues. In America, 53 languages have become extinct since 1950, more than in any other country.

Preserving Languages Is About More Than Words

[syndicated version: World's Languages Become Ever Fewer]

By Kari Lydersen

Washington Post

March 16, 2009

The traditional Irish language is everywhere this time of year, emblazoned on green T-shirts and echoing through pubs. But Irish, often called Gaelic in the United States, is one of thousands of "endangered languages" worldwide. Though it is Ireland's official tongue, there are only about 30,000 fluent speakers left, down from 250,000 when the country was founded in 1922.

Irish schools teach the language as a core subject, but outside a few enclaves in western Ireland, it is relatively rare for families to speak it at home.

"There's the gap between being able to speak Irish and actually speaking it on a daily basis," said Brian O'Conchubhair, an assistant professor of Irish studies at the University of Notre Dame who grew up learning Irish in school. "It's very hard to find it in the cities; it's like a hidden culture."

Irish is expected to survive at least through this century, but half of the world's almost 7,000 remaining languages may disappear by 2100, experts say.

A language is considered extinct when the last person who learned it as his or her primary tongue dies. Last month, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) launched an online atlas of endangered languages, labeling more than 2,400 at risk of extinction.

Hot spots where languages are most endangered include Siberia, northern Australia, the North American Pacific Northwest, and parts of the Andes and Amazon, according to the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages, a nonprofit partnering with National Geographic to record and promote disappearing tongues.

Language extinction has been a phenomenon for at least 10,000 years, since the dawn of agriculture.

"In the pre-agricultural state, the norm was to have lots and lots of little languages," said Gregory D.S. Anderson, director of the Living Tongues Institute. "As humans developed with agriculture, larger population groups were able to aggregate together, and you got larger languages developing."

Languages typically die when speakers of a small language group come in contact with a more dominant population. That happened first when hunter-gatherers transitioned to agriculture, then during periods of European colonial expansion, and more recently with global migration and urbanization. The spread of English, Spanish and Russian wiped out many small languages.

"As long as people feel embarrassed, restrained or openly criticized for using a particular language, it's only natural for them to want to avoid continuing to do what's causing a negative response, whether it's something overt like having your mouth washed out or more subtle like discrimination," Anderson said.

Russian-language-only policies have virtually extinguished many Siberian languages, including Tofa, which lets speakers use a single word to say "a two-year-old male, un-castrated, ridable reindeer."

In the United States and Australia in past decades, the government forced native peoples to abandon their languages through vehicles such as boarding schools that punished youth for speaking a traditional tongue. Many Native American and aboriginal Australian languages never recovered. The United States has lost 115 languages in the past 500 years, by UNESCO's count, 53 of them since the 1950s. Last year, the Alaskan language Eyak disappeared with the death of the last speaker.

Indigenous groups also may abandon localized tongues for a dominant indigenous alternative, such as Quechua in South America. Or they might shift to a pidgin, or hybrid, of various local languages.

Extinct languages can be revived, especially when they have been recorded.

"But when you skip a generation, it's hard to pick a language back up again," said Douglas Whalen, president of the Endangered Language Fund, which gives grants to language-preservation projects. "You need a community that is really committed and will bring children up from birth in the second language, even if they themselves are not the most fluent speakers."

Michael Blake, an associate professor of philosophy and public policy at the University of Washington, said languages have always changed and disappeared over time, and he argues against the idea that all languages should be preserved.

"When we have indigenous languages in danger because of what we've done to these communities, that's the real reason" behind preservation pushes, he said. "But it's a much more complicated argument. It doesn't mean every language now has the right to be immortal."

[syndicated version in association with L.A. Times stops here]

Preservation proponents say there are cultural and pragmatic reasons to save dying languages. Many indigenous communities have in their native tongues vast repositories of knowledge about medicinal herbs, information that could provide clues to modern cures. The Kallawaya people in South America have passed on a secret language from father to son for more than 400 years, including the names and uses of medicinal plants. It is now spoken by fewer than 100 people. Preserving languages is also key to the field of linguistics, which could offer a window into the workings of the brain.

The Living Tongues Institute recruits youth who are not fluent in their traditional tongue to become "language activists," using digital equipment to document their elders' voices and learn the language themselves. This creates a record and builds pride in the language.

Such pride has been key to a modest popular resurgence of the Irish language. Paddy Homan, an Irish musician and social worker who immigrated to Chicago two years ago, thinks the 1990s' "Celtic Tiger" economic boom was a major boost for Irish.

"It used to feel like a sin to speak the Irish language; the English made us feel bad about ourselves, like we were just a nation of alcoholics," said Homan, 34. "Now we feel proud, and speaking Irish is the fashionable thing to do."

Kari Lydersen published a book focusing on the concrete effects of globalization on Latin Americans in their home countries and in the US: Out of the Sea and Into the Fire: Latin American-US Immigration in the Global Age. She writes for The Washington Post, In These Times, the Chicago Reader, Punk Planet, The New Standard News, LiP Magazine, and others. Her website is karilydersen.com

* * * * *

References:

"Speaking in fewer tongues (Daily chart)" economist.com

"Preserving Languages Is About More Than Words"

washingtonpost.com

This article is published under Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. See the Fair Use Notice for more information.